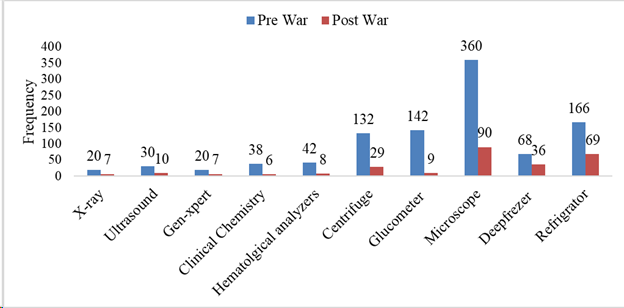

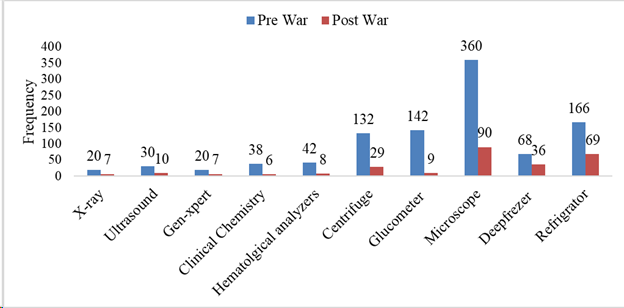

Figure 1 The number of functional medical equipment in the health facilities of the Amhara region, 2022

Violence against Healthcare during the War in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia

1Amhara Public Health Institute, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

2 College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Molalign Tarekegn Minwagaw, email: tamolalign@gmail.com,

Background: Depriving health care through damaging the health facilities' infrastructure, supplies, warehouses, and transport, and targeting the health workforce during war is a serious violation of international humanitarian law. This survey was conducted to assess the damages and service interruptions to the health services in the Amhara region's war zones following the broke out of the war between Ethiopia's central government and the Tigray forces in late 2020.

Methods: The survey was carried out in seven zones and one city administration of the Amhara region. Quantitative data on the extent of destruction were collected from 113 accessible hospitals and health centers using a semi-structured checklist. Furthermore, qualitative data were obtained from twenty-one local administrative heads of zonal health departments, district health offices, hospitals, and health center administrators. The quantitative data were coded, cleaned, and analyzed using SPSS version 24 software. The transcribed qualitative data were translated, coded, and thematically analyzed.

Result: Deliberate destruction of buildings, electrical power supplies, and water sources was noted in 92%, 85%, and 64% of the health facilities respectively. Medical equipment, computers, and other devices were looted from 94% of the health facilities. In addition, 24 ambulances were damaged, and 34 were looted. Healthcare services were disrupted in the majority of health facilities. The healthcare workforces were compelled to evacuate, and experienced kidnappings, torture, and fatalities.

Conclusion: The war broke out in the northern part of Ethiopia deprived the healthcare service from the community. The health workforces were intentionally attacked, and many of the health facilities' infrastructure, ambulances, and medical equipment were looted and destroyed requiring urgent and collective efforts to restore the health service.

Keywords: Violence against health care, war, health facilities damage, health care service interruptions.

የጥናቱ መግቢያ፡- በጦርነት ወቅት የጤና ተቋማትን ያለመ ጥቃት ማድረስ ዘላቂ የእድገት ግቦች ለማሳካት ከሚደረጉ ጥረቶች የሚገታ እንዲሁም ከባድ ዓለም አቀፍ የሰብዓዊነት ህግ ጥሰት ነው። ይህ የዳሰሳ ጥናት የተካሄደው እ.አ.አ. በ2020 መጨረሻ ላይ በማዕከላዊ የኢትዮጵያ መንግሥትና በህወሓት መካከል በተከሰተው ጦርነት በአማራ ክልል በጦርነት የተጐዱ ዞኖች በሚገኙ ጤና ተቋማት ላይ የደረሰውን ውድመትና የጤና አገልግሎት መቋረጥ ለመግለጽ እና ለመተንተን ነው።

የጥናቱ ዘዴ፡- ይህ የዳሰሳ ጥናት በጦርነት ጉዳት በደረሰባቸው ስድስት ዞኖችና አንድ የከተማ አስተዳደር የተካሄደ ሲሆን ተደራሽ በሆኑ 113 ሆስፒታሎች እና ጤና ጣቢዎች መጠናዊ እና አይነታዊ መረጃዎች ተሰብስበዋል፡፡

የጥናቱውጤት፡-በጥናቱ ከተካተቱት ጤና ተቋማት መካከል 92 በመቶ የህንጻ፣ 85 በመቶ የኤሌክትሪክ መብራት መስመር እና 64 በመቶ የውሀ መስመር ዝርጋታ ጉዳት ደርሶባቸዋል፡፡ በ 94 በመቶ የጤና ተቋማት የህክምና መሳሪያዎች፣ ኮምፒውተሮች እንዲሁም ሌሎች አስፈላጊ ህክምና ቁሳቁሶች ተዘርፈዋል፡፡ ሀያ አራት አምቡላንሶች ጉዳት ሲደርስባቸው ሰላሳ አራቱ ተዘርፈዋል፡፡

የጥናቱ ማጠቃለያና ምክረሐሳብ፡- ከጦርነቱ ጋር በተያያዘ በርካታ የጤና ተቋማት ወድመዋል፡፡ የጤና ባለሙያዎች ከስራ ቦታቸው ለመሸሽ፣ለመታገት፣ ለስቃይ እንዲሁም ለሞት ተዳርገዋል፡፡ በዚህም በጤና ተቋማቱ የህክምና አገልግሎት ተስተጓጉሏል፣ ተቋርጧል፡፡ ስለሆነም የወደመውን የጤና መሠረተ-ልማት መልሶ በመገንባት እና ለህክምና ባለሙያዎችን የአእምሮ ጤና ስልጠና በመስጠትና የህክምና አገልግሎቱ በሙሉ አቅም እንዲጀመር ለማድረግ በርብርብ መስራት ያስፈልጋል፡፡

ቁልፍ ቃላት፡ ጦርነት፣ ጤና ተቋም፣ ውድመት፣ ዝርፊያ፣ የጤና አገልግሎት

Targeting healthcare during conflicts by damaging facilities, depleting supplies, destroying warehouses, and disrupting transport is a severe breach of international humanitarian law. It undermines the global endeavor to achieve health for all, justice, and peace 1. Some scholars have characterized such actions as practices of a ‘dirty war 2.

Despite constituting serious violation of human rights and international humanitarian law, the use of violence against healthcare has become an increasingly common approach, effectively weaponizing it by denying medical care to affected populations 3. Conflict reports from various regions have described targeted actions against health workers, facilities, and ambulances.

The Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition’s report, which surveyed 43 countries, recorded 128 health facilities damaged, 51 health transports destroyed or damaged, and 26 hijacked or stolen 4.

In Syria’s conflict, the pattern of targeting health services is alarmingly repetitive. Around 44% of hospitals and 5% of all primary care clinics have been attacked. And, 243 ambulances were intentionally damaged during the hostilities5.

Similarly, the conflict in Afghanistan led to the closure of 140 health facilities that served two million people, enforced by armed factions 6. During the conflicts in Yemen and Chechnya, 102 and 124 healthcare facilities were damaged, respectively 7.

Ethiopia is the second-most populous country in Africa, next to Nigeria, with an estimated population size of 120,116,835 in 2022 8. The government has been enacting policies aimed at enhancing the population’s health, which includes decentralizing health service delivery, expanding the primary healthcare network, and fostering public-private partnerships 9. The number of health services facilities has grown from a total of 2,600 in 1997 to 21,154 (which included 314 hospitals, 3,678 health centers, and 17,162 health posts and private health facilities) in 2019 10.

The Amhara region is Ethiopia's second-most populous region, with an estimated population of 22, 876, 99911. It is composed of 22 zones and city administrations. In 2022, it had 99 hospitals, 924 health centers, and 3679 health posts12.

The armed conflict in Ethiopia broke out in late 2020 between the central government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. It has been ongoing ever since with battles spreading out to the Amhara region. All the districts in Waghimira, North Wollo zones, and Dessie city administration were entirely conflict zones. In addition, most of the South Wollo and North Gondar districts partly experienced the conflict. Within these impacted zones, the healthcare network comprises 38 hospitals, 406 health centers, and 1,634 health posts 13. Therefore, this assessment aimed to describe the extent of the damage inflicted upon health facilities and the health service provision in the conflict-ridden areas of the Amhara region.

A mixed study approach was used to address the study's objective from December 24, 2021, to January 14, 2022, in the war-affected seven zones of the Amhara region. This includes North Wollo, South Wollo, North Gondar, South Gondar, Oromo special Zone, North Shoa, Wagehimera Zone, and Dessie Town.

The source population for the assessment encompassed all health facilities within the war affected zones of Amhara region.

The study population consisted of all hospitals and health centers accessible in the war zones of the Amhara region.

One hundred thirteen accessible health facilities in the war-affected zones were identified and twenty-one Key Informant Interview (KII) participants were recruited through purposive sampling.

Initially, all war-affected areas were planned to be included. However, North Gondar and part of Waghemira zones were excluded due to security concerns during the study period (December 24, 2021, to January 14, 2022).

The quantitative assessment tool and key informant interview guide were initially prepared in English, translated into the local language, Amharic, and then back-translated into English. Each data collector verified questionnaire completeness at the completion of each visit to the health facilities under study. Each questionnaire was reviewed daily for completeness and clarity. For the qualitative component, key informant interviews were conducted post obtaining written informed consent from each participant, using a structured guide. A digital audio recorder was used to capture participants' own words. In addition, notes were taken to capture the feelings and expressions of the participants. Participants were encouraged to share using conversational prompts. Transcriptions of audio records were done daily. All data collectors and supervisors were second and third-degree holders in health-related fields and had rich experience in data collection.

To maintain quality, a comprehensive two-day training session was provided to data collectors and supervisors prior to commencing data collection, with rigorous supervision throughout the process.

Trustworthiness was upheld by adhering to the principles of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. To establish credibility, the researchers employed triangulation, iterative questioning, member checking, and debriefing. Additionally, data collectors possessed a deep understanding of the cultural and social contexts related to the topics. Different participant groups, including health institution authorities at different levels, offered diverse perspectives on the research topics, leading to triangulation. Member-checking sessions were arranged to present initial findings to participants, giving them the opportunity to validate and adjust the data. To enhance transferability, the study included thorough descriptions to offer comprehensive insights into the research context, facilitating the application of findings across various settings, circumstances, and scenarios. To ensure dependability and consistency, overlapping methods like key informant interviews were utilized.

The collected data was entered coded, cleaned, and analyzed using SPSS version 24 software. Descriptive analysis was done and results were presented in frequency tables, graphs, and statements. For qualitative analysis, key informant interviews were transcribed verbatim in Amharic, the local language, and later translated into English for analysis. Thematic analysis was employed for data analysis, starting with multiple readings of transcripts to deeply grasp content and context. Initially, the transcripts were read multiple times to gain a thorough understanding of the content and context. Following this, meaning units were extracted from the transcripts, representing distinct segments of text that captured specific ideas or themes. These meaning units were then condensed, reducing the length of the original text while preserving the core meaning. Subsequently, codes were assigned to these condensed meaning units, and these codes were grouped into categories based on shared themes. This systematic approach facilitated the identification and organization of overarching themes within the data.

The results were categorized into the following three themes:

In war-affected areas of the Amhara region, most health facilities' infrastructure and medical equipment were damaged. The buildings of one hundred and three (91.2%) health facilities were damaged (Table 1). As participants explained, there were health facilities destroyed by heavy weapons.

“The armed groups built their fortress in the health center compound. It was heavily attacked during the war. Maternity and emergency unit buildings were entirely damaged. Most of the roofs were also distracted.” (Source: 35 years old, male, district health office)

“…You can see the broken doors and windows of the OPDs and other offices; you can’t lock them.” (Source: 32 years old male, Hospital)

In the war-affected zones of Amhara region, damage to essential infrastructure like electricity and water supply systems was significant. Electricity systems were affected in 96(85%) health facilities, while water supply systems were also damaged in 73 (64%) facilities Additionally, 22 generators were looted, and 48 facilities lost their power sources completely (Table 1). Some of this damage, as described by a key informant interview participant, was attributed to gun attacks.

“… huge guns had damaged the water supply lines in health facilities.” (Source: 33 years old male, Zonal health department)

The Health Management Information System (HMIS) faced challenges, with 94(83%) health facilities experiencing damage (Table 1). Qualitative insights from a study participant could provide further context or details regarding the impact on HMIS functionality and data management in these facilities as follows:

“There is no patient medical data; all are damaged. The hard disks of office computers’ are looted.” (Source: 43 years old, male, district health office)

Table 1 Health infrastructure damage by zone and health facilities in the war-affected areas of the Amhara region, 2022

| Zone | Facility (n) | Damage type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building | Electric power | Water source | HMIS | ||

| Dessie town | HC (7) | 7(100.0%) | 6(85.7%) | 3(42.9%) | 6(85.7%) |

| Hospital (2) | 2(100.0%) | 2(100.0%) | 1(50.0%) | 1(50.0%)) | |

| North Shewa | HC (12) | 11(91.7%) | 11(91.7%) | 6(50.0%) | 12(100.0%) |

| Hospital (5) | 5(100.0%) | 4(80.0%) | 3(60.0%) | 5(100.0%) | |

| North Wollo | HC (19) | 14(73.7%) | 18(94.7%) | 16(84.2%) | 14(73.4%) |

| Hospital (6) | 4(66.7%) | 5(83.3%) | 5(83.3%) | 5(83.3%) | |

| Oromo Special Zone | HC (3) | 2(100.0%) | 2(100.0%) | 1(50.0%) | 2(66.7%) |

| Hospital (2) | 2(100.0%) | 1(50.0%) | 1(50.0%) | 1(50.0%) | |

| South Gondar | HC (8) | 8(100.0%) | 7(87.5%) | 4(50.0%) | 7(87.5%) |

| Hospital (1) | 1(100.0%) | 1(100.0%) | 1(100.0%) | 1(100.0%) | |

| South Wollo | HC (38) | 37(97.4%) | 29(76.3%) | 14(36.8%) | 34(89.5%) |

| Hospital (3) | 3(100.0%) | 2(66.7%) | 2(66.7%) | 2(66.7%) | |

| Waghimira | HC (5) | 5(100%) | 6(100.0%) | 3(50.0%) | 3(60.0%) |

| Hospital (2) | 2(100.0%) | 2(100.0%) | 2(100.0%) | 1(50.0%) | |

| Total | HC (95) | 84(91.3%) | 79(85.9%) | 47(51.1%) | 81(85.3%) |

| Hospital (18) | 19(90.5%) | 17(81.0%) | 15(71.4%) | 13(72.2%) | |

| Total | 103(91.2%) | 96(85.0%) | 73(64.6%) | 94(83.2) | |

“All medical equipment like ultrasound, microscope, hematological analyzers, gen-expert machine and other medical equipment in our district were damaged.” (Source: 40 years old, male, district health office)

“If you observe Tefera Hailu Hospital, the damage looks simple from the outside, but the microscope, X-ray machines, and other medical equipment are dismantled, and its main parts are looted. You can also observe the case in Ziquala Hospital. It is the same.” (Source: 38 years old, male, Zonal health department)

Some participants described the contamination of service delivery rooms and medical equipment with human fecal matter.

“The maternity and child health care delivery units were targeted. The labor and delivery rooms are damaged, and it is filled with human fecal matter.” (Source: 43 years old, male, district health office)

With the exception of a few, the majority of health professionals were forcibly displaced from their localities for extended periods. They were killed, kidnapped and tortured. In addition, most of the healthcare workers’ properties were lost.

“…One of the critical issues after the war was gathering the healthcare workers from the place they hide’. Totally, 9 health professionals were injured, and 5 died." (Source: 33-year-old male, Zonal health department).

“…The houses of three health professionals were completely damaged”. (Source: 32 years old male, district health office).

“... We have lost one health worker at Kombolcha 03 health center [either kidnapped or killed], and similarly, the ambulance driver at Kombolcha 05 health center was injured’’. (Source: 35 years old male, district health office).

In the war-affected areas of the Amhara region, services were disrupted for an extended period. Despite the return of most healthcare workers to their healthcare facilities after the conflict, service restoration was delayed in these regions.

“When the armed groups entered the town, we were attending a laboring mother. We tried to help by moving her to an individual’s house, but the armed group followed us there. Due to these, we were forced to send her to Tulu Awlia Health Center [25 km away]. However, at that time, the health center was under the control of the armed groups. We heard that after some follow up there, both the mother and her child died” (Source: 27 years old, male, health center)

“HIV patients who discontinue their treatment were traced to come back. However, still 50 patients remain” (Source: 30 years old male from Gazo Woreda health office)

“Since both of the glucometers were looted, we are currently referring suspected cases and those on the follow-up to Adjibair Kollo Genet HC and Tenta hospital [17 km far].” (Source: 45 years old, male, health center head)

Amhara region is known for communicable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV 14-16. It harbors the largest population of individuals living with HIV in the country 17. Addressing malnutrition remains a significant challenge in the region 18.

Despite such huge health problems, tremendous efforts were made to decrease morbidity and mortality and improve the region's health status. Expansion of the health facilities was one of the major efforts and achievements made in the region. The number of health facilities in the region increased rapidly throughout the region 19, 20. There are 90 hospitals, 890 health centers, and 3679 health posts in the region12. In the current health tier system of Ethiopia, the number of people expected to be served is 15,000 -25,000 (health center), 60,000-10,000 (primary hospital), 1-1.5 million (general hospital), and 3.5-5 million (specialized hospital) people 21.

However, the war between the Ethiopian government and the armed Tigray forces which started in late 2020, posed a significant challenge to the effort made to reduce morbidities and mortalities and improve the health of the people in the region 22.

The war lasted months in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, specifically in the six zones. The seven war affected zones contained 38 hospitals, 406 health centers, and 1634 health posts.

The war in the northern part of Ethiopia deprived the healthcare service of the community in the war-affected zone in the Amhara region. It interrupted health service provisions in most of the health facilities. The war resulted in massive destruction of the health system. The health workforce was displaced, kidnapped, and killed during the war. Many health facilities’ infrastructures, including buildings, medical equipment, and health management information systems, were damaged. Diagnostic medical equipment, such as X-ray machines, Gen-expert machines, hematology analyzers, clinical chemistry machines, and microscopes, was damaged and looted in most health facilities. The patient’s medical record management system and the telecommunication system were disrupted.

To resume health service delivery in the war zone, the Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau, in collaboration with partners, must work on restoring the damaged health facilities' infrastructure and medical equipment. In addition, frequent mental health training should be provided for healthcare professionals working in the region's war zones.

Further studies are required to estimate the impact of those service interruptions on the community's health outcomes, including maternal death, pregnancy outcomes, and communicable and non-communicable disease outcomes.

First and foremost we would like to acknowledge the study participants for dedicating their time and providing valuable Information. We also would like to acknowledge data collectors and supervisors. Finally, we would like to extend our acknowledgment to the Amhara Public Health Institution Ethical Review Board and the respective zonal and district health offices for scientifically reviewing and providing ethical clearance and support letters respectively.

KII: Key Informant Interview

SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

Ethical clearance and approval were obtained from the institutional review board of Amhara National Regional State Public Health Institute with reference number No.H/R/T/T/D/5/24 In addition; a support letter was obtained from the respective zonal health departments.

Not applicable.

The data is available upon reasonable request.

.The authors declare no competing interests.

No fund. The data collection cost was covered by the Amhara National Regional State Public Health Institute.

MTM, KM, TZ, DS, GMA, MB, BB, ZA, SA, BB, MY, and GY conceptualized and developed the protocol. MTM, KM, and AM are involved in data analysis and draft manuscript preparation. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

MTM has Master’s degree in Public Health.