Impact of War on Maternal Health Services in the War Affected Areas of the Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Disruption of Antenatal Care, Institutional Delivery and Postnatal Services

Getu Degu Alene 1, 2, Girum Meseret Ayenew 1, Getasew Mulat Bantie1, Taye Zeru1, Gizachew Yismaw1

1 Amhara National Regional State Public Health Institute

2 College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University

*Correspondence Author: Getu Degu (PhD), Bahir Dar University, email : adgetu123@yahoo.com

Background: Health service delivery strategies such as the continuum of care (Antenatal care, delivery and Postnatal care services) are recommended as important components of strong health systems, needed to prevent and reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. The Amhara region has been struggling to improve the continuum of care to the utmost of its ability. Sadly, the ongoing efforts were disrupted as a result of the armed conflict that started in July 2021 in North Wollo and Wag Hemira zones. When the armed conflict was expanded up to north Shewa in December 2021, the damage on the health delivery system and other infrastructures was enormous and inconceivable. In relation to the disruption of health services in Amhara region, there was no study of this kind that attempted to explore the lived experiences of the mothers, health workers and the population at large.

Objectives: The aims of this study were to compare the Antenatal care, delivery and Postnatal care services provided before and during the war periods and to explore the impact of the war on the lives of women that desperately needed maternal health services during the war period.

Methods: The present study included two sources of data: primary and secondary. The primary data which consisted of 22 key informant interviews were collected through the application of purposive sampling. Twenty-four data collectors with at least a first degree in public health or related fields were involved in data collection. On the other hand, the secondary (quantitative) data were obtained from the regional health bureau and the zonal health departments of the war affected zones. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data. Tabular and graphical representations were used to present the findings from the quantitative data. Moreover, in relation to the delivery services, a 95% confidence interval and a P-value were used to declare statistical significance.

Results: The overall continuum of care has shown a significant difference between the pre and during war periods. Before the onset of the war, all Antenatal care, delivery and Postnatal care services were given in all health facilities of the Amhara region. However, only 53 (46.9%) health facilities remained to provide these services in the war-affected areas of the Amhara region. Before the armed conflict, the monthly average number of women who used Antenatal care services at least once in the last six months prior to the eruption of the war was 28,891. However, following the armed conflict, the monthly average of Antenatal Care users was reduced to 10,895 (i.e., a reduction by 62.3%). Similarly, the monthly average number of births attended by skilled health personnel before the armed conflict was 18,527. However, at the climax of the war, this figure was reduced to 5,062 resulting in a reduction of the delivery service by 72.7%. This reduction was statistically significant, (95% C.I. 9828, 17101; P = 0.002). By the same token, the monthly average number of women who received Postnatal care services within seven days of delivery in war affected zones of Amhara region had substantially reduced during the period of the war (a 71.8% reduction).

Conclusion: The damage that the armed conflict brought on the health delivery system of the war-affected zones of the Amhara region was very huge. The armed conflict had terribly affected the delivery of the continuum of care living aside thousands of innocent mothers without any medical assistance. The restoration of the health delivery system and the replacement of the looted and destroyed items should be a priority agenda for the concerned bodies. Furthermore, a mechanism should be developed to give psychosocial support to the needy population.

Keywords: War, Maternal Health, Amhara Region, Ethiopia.

የጥናቱ ዳራ፡ የጤና አገልግሎት አሰጣጥ ስልቶች እንደ ቀጣይነት ያለው እንክብካቤ (የቅድመ ወሊድ፣ የወሊድ እና የድህረ ወሊድ አገልግሎት) የእናቶች ህመም እና ሞትን ለመከላከል እና ለመቀነስ የሚያስፈልጉ ጠንካራ የጤና ስርዓቶች አካላት ሆኖ ይመከራል።የአማራ ክልል አቅሙን ሁሉ በመጠቀም ቀጣይነት ያለው የጤና አገልግሎትና እንክብካቤ ለማሻሻል ሲታገል ቆይቷል። በሚያሳዝን ሁኔታ በሰሜን ወሎ እና ዋግህምራ ዞኖች በሀምሌ 2021 እ.ኤ.አ በጀመረው የትጥቅ ግጭት ምክንያት የተጀመረውን የጤና አገልግሎትና እንክብካቤ ጥረት አስተጓጉሏል። በታህሳስ ወር 2021 የትጥቅ ግጭት እስከ ሰሜን ሸዋ ሲስፋፋ በጤና አሰጣጥ ስርዓቱ እና በሌሎች መሰረተ ልማቶች ላይ የደረሰው ጉዳት እጅግ በጣም ብዙ እና ሊታሰብ የማይችል ነበር። በአማራ ክልል ካለው የጤና አገልግሎት መቆራረጥ ጋር በተያያዘ የእናቶችን፣የጤና ባለሙያዎችን እና የህብረተሰቡን አጠቃላይ የህይወት ተሞክሮ እና ውጣ ውረድ ለመቃኘት የተደረገ ጥናት የለም። ስለሆነም የዚህ ጥናት አላማ በአማራ ክልል በጦርነት በተጎዱ ዞኖች የቅድመ ወሊድ፣ የወሊድ እና የድህረ ወሊድ እንክብካቤ አገልግሎቶችን ከጦርነቱ በፊት እና በነበረበት ወቅት በማነፃፀር በጦርነቱ ወቅት የእናቶች ጤና አገልግሎት በሚያስፈልጋቸው እናቶች ላይ ያደረሰውን ተፅዕኖ ለመዳሰስ ነበር።

የጥናቱ ዘዴዎች፡ የአሁኑ ጥናት ሁለት የመረጃ ምንጮችን ያካትታል-የመጀመሪያ እና ሁለተኛ የመረጃ ምንጭ.። ከሃያ ሁለት ቁልፍ የመረጃ ሰጭዎች መረጃዎች ተሰብስበዋል። በሕብረተሰብ ጤና ወይም ተዛማጅ ዘርፎች ቢያንስ የመጀመሪያ ዲግሪ ያላቸው 24 የመረጃ ሰብሳቢዎች በመረጃ አሰባሰብ ሂዴት ላይ ተሳትፈዋል። በሌላ በኩል የሁለተኛ ደረጃ የመረጃ ምንጭ የተገኘው ከክልሉ ጤና ቢሮ እና በጦርነት ከተጎዱ ዞን ጤና መምሪያዎች ነው። ሃሳቦችን በየፈርጁ (ቲማቲክ) ትንተና ጥቅም ላይ ውሏል። አሃዛዊ (ኳንቲታቲቭ) መረጃ ግኝቶችን ለማቅረብ ሠንጠረዥ እና ስዕላዊ መግለጫዎች ጥቅም ላይ ውለዋል። በተጨማሪም ከአገልግሎት አቅርቦት ጋር በተያያዘ፣ 95% የመተማመን ክፍተት (CI) እና ፒ-ቫልዩ ስታቲስቲካዊ ጠቀሜታን ለማሳየት ጥቅም ላይ ውለዋል።

የጥናቱ ውጤቶች፡- አጠቃላይ የአገልግሎት አሰጣጥና እንክብካቤ ቀጣይነት በቅድመ እና በጦርነት ጊዜ መካከል ከፍተኛ ልዩነት አሳይቷል። ጦርነቱ ከመጀመሩ በፊት በሁሉም በአማራ ክልል ባሉ ሁሉም የጤና ተቋማት የቅድመ ወሊድ፣ የወሊድ እና የድህረ ወሊድ አገልግሎት ይሰጡ ነበር። ነገር ግን በአማራ ክልል ጦርነት በተከሰተባቸው አካባቢዎች እነዚህን አገልግሎቶች ለመስጠት 53 (46.9%) የጤና ተቋማት ብቻ ቀርተዋል። ከትጥቅ ግጭት በፊት፣ ማለትም ጦርነቱ ከመከሰተቱ በፊት ባለፉት ስድስት ወራት ውስጥ ቢያንስ አንድ ጊዜ የቅድመ ወሊድ እንክብካቤ አገልግሎትን የተጠቀሙ እናቶች ወርሃዊ አማካይ ቁጥር 28,891 ነበር። ነገር ግን፣ የትጥቅ ግጭትን ተከትሎ፣ የቅድመ ወሊድ አገልግሎት ተጠቃሚዎች ወርሃዊ አማካይ ወደ 10,895 (ማለትም፣ በ62.3%) ቀንሷል። በተመሳሳይ ከትጥቅ ግጭት በፊት በሰለጠነ የጤና ባለሙያዎች የሚሰጥ የወሊድ አገልግሎት ወርሃዊ አማካይ የወሊድ ቁጥር 18,527 ነበር። ነገር ግን በጦርነቱ ጫፍ ላይ ይህ አሃዝ ወደ 5,062 በመቀነሱ የአቅርቦት አገልግሎት በ72.7 በመቶ ቀንሷል። ይህ ቅነሳ በስታቲስቲክስ ጉልህ ነበር (95% C.I. 9828, 17101; P = 0.002). በተመሳሳይ መልኩ በአማራ ክልል በጦርነት በተጎዱ ዞኖች ከወሊድ በኋላ በሰባት ቀናት ውስጥ የድህረ ወሊድ አገልግሎት የሚያገኙ እናቶች ወርሃዊ አማካይ ቁጥር በከፍተኛ ሁኔታ ቀንሷል (በጦርነቱ ወቅት 71.8 በመቶ ቅናሽ አሳይቷል)።

የጥናቱ ማጠቃለያና ምክረ ሀሳቦች፡ የትጥቅ ግጭት ወይም ጦርነት በተከሰተባቸው በአማራ ክልል ዞኖች የጤና አገልግሎት አሰጣጥ ስርዓት ላይ ያደረሰው ጉዳት እጅግ ከፍተኛ ነበረ። የትጥቅ ግጭት በሺዎች የሚቆጠሩ ንፁሀን እናቶችን ያለ ምንም የህክምና እርዳታ የሚኖረውን ቀጣይነት ያለው እንክብካቤ አሰጣጥ ላይ ክፉኛ ጎድቷል። የጤና አሰጣጥ ስርዓቱን ወደነበረበት መመለስ እና የተዘረፉ እና የተበላሹ እቃዎች መተካት የሚመለከታቸው አካላት ቀዳሚ አጀንዳ ሊሆን ይገባል። በተጨማሪም ለተቸገረው ህዝብ የስነ-ልቦና ድጋፍ የሚሰጥበት ዘዴ ሊዘጋጅ ይገባል።

የጥናቱ ቁልፍ ቃላት፡- ጦርነት ፣ የእናቶች ጤና አገልግሎት ፣ አማራ ክልል ፣ ኢትዮጵያ

Maternal health refers to the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period. Each stage should be a positive experience, ensuring women and their babies reach their full potential for health and well-being. Improving the lives of mothers has been an important public health and development agenda in the world in general and in Ethiopia in particular.1,2 Many studies have shown that enhancing the uptake of maternal health services helps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. Maternal death highly affects families, communities and it negatively impacts the economic development of countries .3-6

Although maternal deaths have significantly decreased in the developed world, it is still unacceptably high in low income countries, particularly in sub-Sahara African countries. Despite proven interventions that could prevent death or disability during pregnancy and childbirth, maternal mortality remains a major burden in many developing countries. Maternal mortality continues to be a major challenge in Africa and the maternal mortality disparity between developing and developed countries is very high. For example, the lifetime risk of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa is 1 in 39, but only 1 in 3800 in high income countries.7

The World Health Organization (WHO) put a global target to reduce Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) to less than 70/100,000 live births (LBs) by 2030 [6,8]. In line with this, the Ethiopian government set a target to reduce it to 199/100,000 Live Births by the end of 2020 and 42/100,000 Live Births by the end of 2035 through provision of improved maternal health services.6, 8-10 In line with this, the Ministry of Health of Ethiopia reported that Ethiopia had made a striding change in maternal death over the last decades. The MMR decreased from 871 per 100,000 in 2000 to 401 per 100,000 in 2017 (this is death of about 12,000 mothers every year).6

Health service delivery strategies such as the continuum of care are recommended as important components of strong health systems, needed to prevent and reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. The continuum of care ensures that services are provided in an integrated manner to reduce duplication of effort and save costs.11, 12

Antenatal Care (ANC), use of skilled delivery attendants and postnatal care (PNC) services are key maternal health services that can significantly reduce maternal mortality. It is usually reported that understanding of the factors that affect service utilization would help to design appropriate strategies so as to improve uptake of maternal health service that would ultimately lead to the reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality .13

Accordingly, WHO prepared a document relating to maternal health that serves as a guideline in responding to two important questions.14 What health interventions should be delivered during pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period? What health behaviors should the women practice (or not practise) during these periods to care for herself and her baby?

Antenatal care: It is the care provided by skilled healthcare professionals to women throughout their pregnancy. It includes risk identification and screening, prevention and management of pregnancy-related or concurrent diseases, and health education and promotion. The ANC4+ indicator is based on a standard question that asks if and how many times the health of the woman was checked during pregnancy. Antenatal care coverage is usually taken as an indicator of access and use of health care during pregnancy.15

Births attended by skilled health personnel: According to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 3.1.2, proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel (doctors, nurses, midwives and other health professionals providing childbirth care) is one of the most important phases in the continuum of care. It is an indicator of health care utilization.16 The latest available data suggest that in highest income and upper middle income countries, more than 90% of all births benefit from the presence of a trained midwife, doctor or nurse. However, fewer than half of all births in several low income and lower-middle-income countries are assisted by such skilled health personnel.16

Postnatal care: The world Health Organization (WHO) stated that postnatal care is defined as a care given to the mother and her newborn baby immediately after the birth of the placenta and for the first 42 days of life. Majority of maternal and neonatal deaths occur during childbirth and postnatal period. However, this period of significant transition remains the most neglected phase in maternal and newborn health care .17,18

The Ethiopian health care delivery system is one of the poorest in the world. This has led the country to extend its hands to foreign assistance to fulfill the minimum health service requirements of its people. The situation of the Amhara region, even before the armed conflict, was a witness for the incompatibility of the delivery of the health services to the ever increasing need of the population. This being the reality on the ground during the pre-war period, the armed conflict which was expanded up to North Shewa had dismantled the staggering health care delivery system in the war affected areas of the region.6,9,10

The experiences of many countries, such as, Pakistan, Kenya, South Sudan, Burundi and Uganda show that war increases the burden by disrupting the existing healthcare system in poor countries where resources are already scarce.19-22 The Tigrean People’s Libration Front armed forces were busy looting and destroying the health facilities of the Amhara region between June 2021 and December 2021, until it was forced to leave most of the areas it occupied.23

The Federal and the Amhara regional governments have been exerting efforts to bring Maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by the year 2030. However, the disruptions of the health care delivery system as a result of the armed conflict left the population of the affected areas without any or very limited access to curative and preventive health services .23-26 Therefore, for effective restoration of these services, credible evidence about the extent of the disruption of maternal health services is of immense importance. Accordingly, the present study examines the impact of the war on maternal health services relating to antenatal, delivery and postnatal care in the war-affected areas of the Amhara region. In line with this, comparisons are made between maternal health services (ANC, delivery and PNC services) provided before and during the war periods. Moreover, the impact of the armed conflict on the lives of women that badly needed maternal health services during the war period is explored.

This study was conducted in the war-affected zones of the Amhara national regional state from December 24, 2021 to January 14, 2022. The survey was carried out in six Zones and one City administration: North Wollo, South Wollo, South Gondar, Oromo special zone, North Shewa, Wag Hemra and Dessie City. A total of 24 public hospitals and 90 health centers were included in the study. That is, one hundred thirteen health facilities that provided maternal health services before the war were investigated. The Amhara National Regional State (ANRS) is one of the eleven regional states in Ethiopia. The ANRS is the second most populous region in Ethiopia.

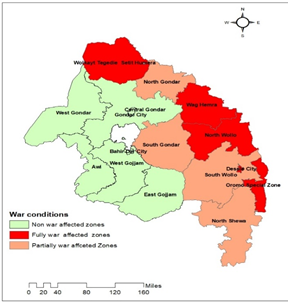

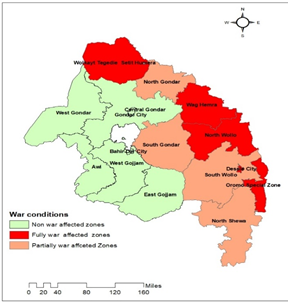

Before the armed conflict, 96 hospitals (86 publics and ten private) were properly functioning. Among the public hospitals, 8 are comprehensive and specialized hospitals, 13 are general hospitals, and 65 are primary hospitals. In addition, 874 public health centers and 3,561 health posts, and over 1,300 private health facilities were giving health services to their respective populations. The map of ANRS with its zones affected by the war is shown in (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of the Amhara region showing the degree of invasion of Zones, 2022

Women residing in the selected districts of the war affected zones/ city administration of the Amhara region who were considered in the survey were the study population. Heads of Zonal and District Health Offices, Hospital directors, Health center heads and health workers who were in charge of the provision of maternal health services (ANC, Delivery and PNC) were considered in the present study.

One hundred thirteen accessible health facilities in the war-affected zones were identified and twenty-two. Key Informant Interview (KII) participants were recruited by purposive sampling.

All war-affected areas were initially planned to be entertained. However, hot spot areas of war in North Gondar and part of Wag Hemira zones were not considered due to security issues during the study (data collection) period (i.e., December 24, 2021 to January 14, 2022).

Primary data sources: A checklist/guideline which was semi-structured by its very nature was used during the collection of the qualitative data through key informant interviews. Moreover, direct observation was also carried out to triangulate the data obtained from the KIIs.

Secondary data sources: Data obtained from the reports of the Amhara Regional Health bureau and Health departments of the war affected Zones (Districts) were considered. In this regard, the secondary data were taken from seven zones (including north Gondar) and Dessie city administration. Note that a Key informant interview was not conducted in north Gondar due to security problems during the time of data collection.

A total of 24 data collectors and six supervisors were selected and trained. All data collectors and supervisors were second and third degree holders in health related fields and had rich experience in data collection. The heads of zonal health departments, district health offices, hospitals and Health centers of war-affected areas were involved in the key informant interview. In addition, patient records were observed when available. The extent of service utilization of clients in the pre and during-war periods was considered.

A two-day training was given to both data collectors and supervisors before data collection, and a strict supervision was carried out. Data quality was guaranteed with proper recruitment, adequate training and close supervision of data collectors.

The collected data were entered in to Epi Data version 3.1, coded, cleaned, and analyzed using SPSS version 24 statistical software. Descriptive statistics were computed, and presented in tables and charts.

In relation to the qualitative data, the recorded interview was transcribed verbatim and translated into English. The principle of data immersion was considered by listening to the audio and reading the transcripts repeatedly. In this regard, the following steps of qualitative data analysis were followed.27

In short, as can be noted from the above explanations, the procedure that we used to process our qualitative data for the purposes of classification, summarization and tabulation was thematic analysis.

Findings from the quantitative studies (Secondary data)

The overall Antenatal care service has shown a big difference between the pre and during war periods. Before the armed conflict, ANC services were given in all health facilities of the war affected areas of the Amhara region. However, only 53 (46.9%) health facilities remained to provide ANC services in the war-affected areas of the Amhara region.

The monthly average number of women who used ANC services at least once in the last six months prior to the eruption of the war was 28,891. However, following the occupation of Wag Hemira and North Wello zones which left them without any maternal health service, the monthly average declined to 21,258. Furthermore, due to the expansion of the armed conflict, three more zones (South Wello, Oromo special, and part of north Shewa) and Dessie city administration were occupied by the Tigrean People’s Libration Front (TPLF) forces. Subsequently, the maternal health services in the completely attacked zones turned out to be zero affecting terribly the lives of women that badly required such services. Ultimately, the monthly average of Antenatal Care users was reduced to 10,895 which was 37.7% of the pre-war period. In absolute terms, the number of women who didn’t get the service was over 87 thousand (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of women who received Antenatal Care services at least once in war affected Zones of Amhara region, January 2021-November 2021

| Month and Year | Number of women who received ANC services at least once in war affected zones of Amhara region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Gondar | South Gondar | North Shewa | Dessie town | South Wollo | Oromo special Zone | North Wollo | Wag Hemira | Total | |

| Jan-21 | 2969 | 4949 | 5371 | 781 | 7158 | 1552 | 3866 | 2043 | 28,689 |

| Feb-21 | 2999 | 5689 | 5774 | 839 | 7280 | 1627 | 4068 | 2070 | 30,346 |

| Mar-21 | 3046 | 5932 | 5692 | 807 | 8089 | 1680 | 4205 | 1725 | 31,176 |

| Apr-21 | 2529 | 5596 | 4646 | 697 | 7501 | 1655 | 3858 | 1694 | 28,176 |

| May-21 | 2104 | 4516 | 4687 | 866 | 7018 | 2027 | 3461 | 1364 | 26,043 |

| Jun-21 | 2564 | 5168 | 5451 | 806 | 7612 | 1968 | 3560 | 1782 | 28,911 |

| Before the TPLF initiated war, the monthly average was 28,891 (i.e., 173,341/ 6 = 28,891). | |||||||||

| Jul-21 | 1633 | 4446 | 5401 | 702 | 6452 | 1681 | 0 | 0 | 20,315 |

| Aug-21 | 1491 | 4221 | 5572 | 950 | 6604 | 1729 | 0 | 0 | 20,567 |

| Sep-21 | 1373 | 4818 | 5975 | 936 | 7784 | 2005 | 0 | 0 | 22,891 |

| Following the occupation of North Wollo and Wag Hemira, the monthly average was 21,258(63,773/ 3 = 21,258). | |||||||||

| Oct-21 | 1940 | 5556 | 4866 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12,362 |

| Nov-21 | 1946 | 4911 | 2571 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9,428 |

The monthly average number of women who used ANC services at least four times before the armed conflict was 20,148. However, following the annexation of Wag Hemira and North Wello zones by the TPLF forces, the monthly average turned out to be 14,562. Furthermore, due to the continued expansion of the armed conflict, three more zones (South Wello, Oromo special, and part of north Shewa) and Dessie city administration were occupied.

The maternal health services in the completely occupied zones turned out to be zero and that had led the monthly average of Antenatal Care users at least four times in the war affected areas to be 5,638 resulting in a reduction of 72% from the pre-war period (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of women who received Antenatal Care services (ANC4, at least 4 visits) classified by Zone e in war affected areas of Amhara region, Jan. 2021-Nov. 2022

| Month and Year | Actual /expected number of women who received ANC4 services in war affected zones of Amhara region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Gondar | South Gondar | North Shewa | Dessie town | South Wollo | Oromo special Zone | North Wollo | Wag Hemira | Total | |

| Jan-21 | 1321 | 3799 | 4154 | 444 | 5958 | 936 | 2859 | 1046 | 20,517 |

| Feb-21 | 1258 | 3798 | 3985 | 431 | 5564 | 1084 | 2621 | 957 | 19,698 |

| Mar-21 | 1605 | 4104 | 3993 | 608 | 6548 | 963 | 2724 | 902 | 21,447 |

| Apr-21 | 1183 | 3758 | 3344 | 471 | 5821 | 932 | 2665 | 923 | 19,097 |

| May-21 | 1098 | 3754 | 3453 | 854 | 5700 | 1109 | 2643 | 824 | 19,435 |

| Jun-21 | 1211 | 3960 | 3858 | 768 | 6045 | 1141 | 2737 | 970 | 20,690 |

| Before the TPLF initiated war, the monthly average was 20,148 (i.e.,120,884 / 6 = 20,148) | |||||||||

| Jul-21 | 721 | 2931 | 3569 | 477 | 5236 | 1057 | 0 | 0 | 13,991 |

| Aug-21 | 740 | 2481 | 3781 | 537 | 5225 | 1180 | 0 | 0 | 13,944 |

| Sep-21 | 661 | 2634 | 4307 | 517 | 6320 | 1310 | 0 | 0 | 15,749 |

| Following the annexation of North Wollo and Wag Hemira, the monthly average was 14,562. (i.e., 43,684/3) | |||||||||

| Oct-21 | 832 | 3165 | 3493 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7,490 |

| Nov-21 | 772 | 2841 | 1880 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,493 |

| Dec-21 | 930 | 3001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,931 |

When the war was further extended (i.e., South Wollo, Oromo special zone and Dessie city were the battlefields), the monthly average turned out to be 5,638. (i.e., 16,914 / 3 = 5,638

The monthly average number of births attended by skilled health personnel before the armed conflict was 18,527. However, following the annexation of Wag Hemira and North Wello zones by the TPLF forces, the monthly average turned out to be 13, 869. Subsequently, when more zones and one city administration were occupied, the figure was reduced to 5,062. This showed a reduction in the delivery service by 72.7%.

In absolute terms, the number of women who were not attended by skilled personnel was over 54 thousand (Table 3). The monthly mean reduction (i.e., before - after = 13,465) turned out to be statistically significant with a 95% C.I. of (9828, 17101) and P-value = .002(Table 3).

Table 3. Number of births attended by skilled health personnel classified by Zone in war affected areas of Amhara region, January 2021-November 202

| Month and Year | Number of women who received Institutional delivery services in war affected zones of Amhara region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Gondar | South Gondar | North Shewa | Dessie town | South Wollo | Oromo special Zone | North Wollo | Wag Hemira | Total | |

| Jan-21 | 1140 | 3534 | 3624 | 907 | 5182 | 1059 | 2427 | 1016 | 18,889 |

| February.2021 | 1192 | 3594 | 3776 | 986 | 5266 | 1075 | 2488 | 1039 | 19,416 |

| Mar-21 | 1094 | 3400 | 3416 | 958 | 5248 | 1002 | 2351 | 872 | 18,341 |

| Apr-21 | 1129 | 3554 | 3165 | 1075 | 5128 | 966 | 2464 | 927 | 18,408 |

| May-21 | 921 | 3066 | 3204 | 1034 | 4933 | 927 | 2286 | 801 | 17,172 |

| Jun-21 | 1101 | 3435 | 3610 | 889 | 5499 | 1039 | 2509 | 849 | 18,931 |

| Before the armed conflict, the monthly average was 18,527 (i.e., 111,157 / 6 =18,526.2) | |||||||||

| Jul-21 | 656 | 2783 | 3168 | 935 | 5000 | 1056 | 0 | 0 | 13,598 |

| August. 2021 | 590 | 2262 | 3254 | 1036 | 4958 | 1062 | 0 | 0 | 13,162 |

| Sep-21 | 601 | 2561 | 3461 | 1116 | 5743 | 1364 | 0 | 0 | 14,846 |

| Following the occupation of North Wollo and Wag Hemira, the monthly average was 13, 869 (i.e., 41,606/3 = 13,868.7). | |||||||||

| Oct-21 | 706 | 2792 | 2945 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6,443 |

| Nov-21 | 755 | 2720 | 2030 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,505 |

| December. 2021 | 716 | 2521 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,237 |

When the armed conflict was extended to South Wollo, Oromo special zone and Dessie city, the monthly average turned out to be 5,062 (i.e., 15,185 / 3 = 5,061.7).

The monthly average number of women who received PNC services within seven days of delivery in war affected zones of Amhara region had tremendously reduced during the period of the armed conflict. For example, the monthly average number of mothers who received PNC services before the war was 25024. However, following the annexation of Wag Hemira and North Wello zones by the TPLF forces, the monthly average turned out to be 17,220 and subsequently when more zones and one city administration were under the control of TPLF forces, the figure was reduced to 7,067. This showed a reduction in the number of PNC users by 31.2% and 71.8% respectively from the usual number under normal circumstances. In absolute terms, the number of women who didn’t get PNC services following the occupation of six zones and one city administration was over 77,000 (Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of women who received PNC services within seven days of delivery in war affected Zones of Amhara region, January 2021-December 2021.

| Month and Year | Actual /expected number of women who received PNC services in war affected zones of Amhara region | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Gondar | South Gondar | North Shewa | Dessie town | South Wollo | Oromo special Zone | North Wollo | Wag Hemira | Total | |

| Jan-21 | 1752 | 5387 | 4313 | 947 | 6234 | 1190 | 4209 | 1423 | 25,455 |

| February. 2021 | 1823 | 5576 | 4560 | 1018 | 6127 | 1304 | 4118 | 1421 | 25,947 |

| Mar-21 | 1755 | 5218 | 4133 | 1008 | 6155 | 1225 | 4122 | 1140 | 24,756 |

| Apr-21 | 1754 | 5457 | 3686 | 1208 | 5957 | 1064 | 3948 | 1149 | 24,223 |

| May-21 | 1507 | 5058 | 3782 | 1034 | 5761 | 1186 | 3877 | 1096 | 23,301 |

| Jun-21 | 1678 | 5754 | 4757 | 724 | 6582 | 1376 | 4322 | 1267 | 26,460 |

| Before the armed conflict, the monthly average was 25,024 (i.e., 150,142/ 6 = 25,023.7). | |||||||||

| Jul-21 | 1058 | 4111 | 3684 | 998 | 5936 | 1278 | 0 | 0 | 17,065 |

| August. 2021 | 831 | 3403 | 3686 | 1169 | 5780 | 1370 | 0 | 0 | 16,239 |

| Sep-21 | 829 | 3785 | 4130 | 1133 | 6860 | 1619 | 0 | 0 | 18,356 |

| Following the annexation of North Wollo and Wag Hemira by the TPLF forces, the monthly average was 17,220 (i.e., 51,660/3 = 17,220). | |||||||||

| Oct-21 | 1115 | 4299 | 3195 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8,609 |

| Nov-21 | 1096 | 4062 | 2189 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7,347 |

| December. 2021 | 1131 | 4114 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5245 |

When the armed conflict was extended to South Wollo, Oromo special zone and Dessie city, the monthly average turned out to be 7,067 (i.e., 21,201 / 3 = 7,067).

A total of 22 key informant interviews were carried out in war affected areas of the Amhara region. As shown in Table 5, participants were purposely selected from different backgrounds so as to make the composition as diverse as possible. This type of arrangement was part of the effort to maintain theoretical representation of the respective Zones in particular and the war affected areas of the region in general. Except for north Gondar which was not covered due to security problems, all other war-affected zones were considered in this qualitative study. Some health facilities in Wag Hemira and North Wello zones located close to Tigray region were not included due to security problems during the time of data collection.

Table 5. Summary of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants of the key informant interviews, Amhara region, December 24, 2021 - January 14, 2022.

| Type of Health Facility | Number of KIIs | Age of Info. | Sex of Info. | Educ. Status | Position of the informant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital (Primary, General and Comprehensive) | 6 | 29-45 | M | MD, 2nd Degree | Medical Director |

| Health Center | 6 | 26-40 | M | 1st Degree | Head /representative of Health Center |

| District Health Office | 7 | 28-50 | M | 1st and 2nd Degree | Head/representative of District Health Office (DHO) |

| Zonal Health Department | 3 | 35-58 | M | 1st and 2nd Degree | Head/ representative, Zonal Health Department (ZHD) |

N.B. All 1st and 2nd degrees refer to Public Health and Nursing professions.

As shown in Table 5, heads/representatives of Zonal Health Departments (ZHD), heads/representatives of District Health Offices (DHO), Hospital Directors, heads of health Centers and other professionals, such as, MNCH Officers were involved in the key informant interviews. By strictly following the steps of thematic analysis, the following major themes were emerged (coded) from the 22 key informant interviews.

Themes (I to IV) that emerged from the analysis of the qualitative data:

Theme I) Interruption of maternal health services: ANC, Institutional delivery and PNC

“When the war broke out in the neighboring district, we told the mothers who were waiting in the maternity waiting room to go home. Later on, we heard that eleven mothers were forced to give birth in caves and in the bushes. “(A 36-year-old health personnel, Head of a Health Center)

“The hospital is now in a position of giving no service including maternal health and EPI services. I am an eye witness that women who were brought to the hospital seeking assistance for delivery services were denied of the required service. Some of the mothers were begging the medical team of the TPLF militant group who was giving medical care to its own fighters. However, the group that controlled the hospital was reluctant to give the service” (A 41-year-old health personnel, Medical director)

“All maternal health services including ANC, Delivery and PNC were discontinued due to the invasion. As I mentioned earlier, our health center used to give delivery services for 15-20 mothers every day.” (A 40-year-old, health center head))

“It is surprising, if you observe Tefera Hailu hospital, the damage looks simple from the outside. But, if you closely observe the situation, you would see that the lenses of the microscope are looted, delivery beds are looted and destroyed, etc. All the services in all health facilities were interrupted.

There were mothers who gave birth in Kewiziba while being displaced from Sekota town” (Age = 35, representative of ZHD)

“At the time of the TPLF’s invasion, all Pre-delivery, delivery and post-delivery services were completely interrupted. Due to this reason mothers had no choice other than delivering in unsafe places. We have a lot of information about unwanted pregnancies, bleeding during home delivery and other complications during labor and delivery.” (A 28 old man, Hospital Director)

All the key informants desperately reported that maternal health services of any kind (ANC, Institutional delivery and PNC services) were interrupted following the armed conflict. The above five quotes which could represent the views of all participants are presented here.

Theme II) Undesirable outcomes: Rape, Disability, Death (mainly, maternal death), etc.

Under this theme, the following quotes were taken to indicate the extent of the problem.

“In the case of maternal health services, for example, mothers who have had antenatal care have stopped following them due to the war and are unable to access the service; as a result, more than four mothers died in July and August due to childbirth. Pregnant mothers who had to be referred to another health facility for surgery could not receive the service, and immunization services were suspended for more than four months”. (Age 27, health center head)

“The war has taken a heavy toll on maternal and child health in 5 months. According to current information, more than 10 mothers in our district have died during childbirth” (A 33 old health personnel, DHO head)

“Before the war, we used to give delivery services for more than 27 mothers per day. The hospital service was closed for 40 days. Three mothers who delivered during the war period have developed fistula and complicated labour” (Age 38, Hospital director)

“We have a report that many mothers died during the war. I know a mother who died because of complicated labour. About 10 newborn children died immediately after delivery because of service interruption. “ (Age 26, Health center head)

“Unfortunately, the areas that are highly damaged are maternal and child health service programs. Our hospital used to give delivery services for nineteen thousand mothers annually. When such services were interrupted for more than half a year, you can imagine the sufferings that women would face during delivery. For example, there is a pregnant woman who died in Sekota town at the time of home delivery. Moreover, there are reports that show the death of over twelve mothers during home delivery”

(…)(A 35 old health personnel, Zonal health department).

As can be understood from the above quotes, the most reported undesirable outcomes were rape and maternal death. Nearly all key informants reported that there were maternal deaths due to lack of medical assistance.

Theme III) Mental (Psychological) disorder: Development of psychological scar (anxiety, depression, PTSD) on both health professionals and mothers/children due to the shocking event they had experienced during the TPLF led war

Because of the war crime done on the civilians in various forms including intimidation and murder, nearly all of the participants of the KIIs reported that many people have developed some kind of psychological disorders. Not only the civilians, but also the health professionals were suffering from the same psychological trauma. The following quotes could say a lot in this regard.

“During the four months of the TPLF invasion, all properties of our hospital including drugs were looted (when conditions permitted) and destroyed (when conditions did not permit). Especially, HIV patients who were under ART have suffered a lot from the discontinuation of the service. Although looting and destroying items is expected from enemies like TPLF, what the terrorists did in our district was beyond imagination. They raped 32 women including the wife of a priest. The psychological trauma that our people have developed will have long-term effects requiring a special attention by the responsible bodies. (A 29-year-old hospital director, second degree holder)

“Not only the ordinary people but also our health professionals who were kidnapped by the terrorist group need psychosocial support.” (A 32-year-old health personnel, Deputy head of DHO)

“Children who were traumatized have quitted attending schools. Mothers who were sexually abused by a group of terrorists in front of their children are highly humiliated and stigmatized. These evil deeds are out of our tradition. Our people are religious and such shameful activities are not accepted by the community.” (A 33-year-old health professional, Head of DHO).

Theme IV) Remedial measures to be taken: Solutions suggested/reported by the informants

All of the participants of the key informant interviews said that they had no words to express the extent of the damage brought by the armed conflicts. All activities relating to maternal health (ANC, Delivery and PNC) services were ruined. The TPLF forces were intentionally destroying everything they found in front of them. When they felt that the laboratory equipment or any other goods are important, there was an organized unit whose sole duty was looting and sending the stolen items to Tigray. After all these destructions, what are the remedial measures to be taken to restore the health delivery system to its former condition? In this regard, one of the key informants had to say the following:

“The TPLF militant group looted everything from our health center. Laboratory equipment, computers, medical supplies including drugs worth of 28 million Eth. Birr that belonged to a non-governmental organization to be distributed among health facilities and people displaced from Kobo and Woldia areas. In this regard, the responsible governmental and non-governmental organizations are requested to play the main role in restoring the dismantled health center to its former condition.” (A 40-year-old Health Officer).

In line with this last theme, nearly all informants emphasized the need that the looted properties should be returned to the owners (health institutions where the looting was carried out).

The present assessment has revealed the fact that over 180 thousand pregnant women who were expected to get ANC, delivery and PNC services in war-affected zones of the Amhara region were unable to receive the services. In fact, this figure is highly likely to increase as most of the health facilities have not started giving the required maternal health services since the withdrawal of the TPLF forces from the war affected areas. This was substantiated by the findings obtained from the key informant interviews. All of the Key informants we interviewed sadly reported that the maternal health services (ANC, delivery and PNC) were totally interrupted due to the damage/demolition of the facilities, closure of the facilities, lack of equipment and supplies, and unstable health care professionals.

The motto that no mother should die while giving life is highly acceptable and appreciable.28 In fact, improving maternal health is one of WHO’s key priorities, grounded in a human rights approach and linked to efforts on universal health coverage. It is true that promoting health along the whole continuum of pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal care is crucial.29 Unfortunately, the facts on the ground are rather different in developing countries including Ethiopia.7

Why do women die? Women die as a result of complications during and following pregnancy and childbirth. Most of these complications develop during pregnancy and most are preventable or treatable. The major complications that account for nearly 75% of all maternal deaths are 30 high blood pressure during pregnancy, complications from delivery, unsafe abortion, severe bleeding and infections after childbirth.

Yes, one cannot deny the contribution of the above factors in worsening the deaths of mothers contrary to the motto “no mother should die while giving life”. On the other hand, it is rather disturbing to report that there is no parallel to the maternal lives lost in Ethiopia due to armed conflicts led by the so-called liberation fronts.

Following the annexation of over half of the Zones of the Amhara region by the TPLF forces, hundreds and thousands of mothers didn’t get the required health services during pregnancy, delivery and after childbirth. This has led to the untimely deaths of many innocent mothers in the war affected areas. Most of these maternal deaths resulting from the lack of medical assistance could have been avoided had it not been for the flare up of the armed conflicts.

As observed in the key informant interviews, pregnant mothers who were on the verge of giving birth were begging the TPLF medical team for some assistance. However, the mothers were denied of the badly needed medical assistance by the militants. It is highly likely that most of these mothers would die while giving life. From the findings of both the quantitative and qualitative approaches, one could infer the degree of the war crime against the innocent people of the Amhara region.31

We cannot deny the impressive progress that has been made in Ethiopia in reducing the risk of maternal death due to complications during delivery since 2000. However, the situation has been reversed in war affected areas of the Amhara region due to the armed conflict which totally (in four zones) and substantially (in three zones) destroyed the infrastructure and put the health delivery system in a complete mess.23,24

The experiences of many countries, such as, Eastern Burma, Nepal, Pakistan and South Sudan show that war increases the burden by disrupting the existing healthcare system in poor countries like Ethiopia where resources are already scarce.32-35 Likewise, the war-affected zones of the Amhara region are suffering from the same phenomena.

According to WHO and other sources, 15% of all pregnant women develop life-threatening complication that calls for skilled care and some would require a major obstetrical intervention to survive. In line with this, there had been over 27,000 mothers in the war affected areas who were exposed to such serious complications and most of these women would have ended up with death as there were no maternal health care services during that time.36, 37 In this regard, it is highly unlikely that Ethiopia will meet both national and international targets.8,10

One could argue that this study might not come up with new knowledge/ideas that would facilitate the restoration of the health delivery system in the war affected areas. The argument could be based on the assumption that the problem (research question) and factors are known and what is remaining is a management issue that requires the undertaking of the necessary action. However, the Amhara Public Health Institute and the experts involved in this research work strongly believe that conducting the present assessment is justifiable. That is, besides documenting the impact of the war on the health delivery system and the agenda behind the armed conflict, the study helps to explore the lived experiences of patients, health workers and the population at large. Moreover, the findings of the present study will guide us to conduct a more focused study that will throw light on the type of intervention to be undertaken.

As can be observed from Table 5, females were not included as part of the qualitative approach and this was taken as one of the limitations of the present study. The lack of independence between the users of maternal health services (ANC and PNC services) before and during the armed conflict and the unavailability of data relating to the characteristics of each individual woman has refrained us from applying a rigorous (conventional) statistical test.

The damage that the armed conflict brought on the health delivery system of the war-affected zones of the Amhara region is very huge.

There is no human being who would deny the appropriateness of the motto, “No mother should die while giving life”. However, such a valuable universal moral principle is neglected at times of war. Many mothers who needed maternal health services of any kind were left helpless due to the discontinuation of the required services. There were no ANC, delivery and PNC services during the time of the war which lasted for several months. The armed conflict has ended up with the tragic death of many mothers who tried to deliver at home or in the bush when conditions didn’t allow home delivery. Besides the dissolution of the health care delivery system, the majority of the people of the war affected areas were left with some kind of psychological distress. Since this is the reality on the ground, the federal government of Ethiopia and the Amhara national regional state should take the obligation to play the greatest role in restoring the looted and destroyed items and restart the discontinued maternal health service in the war affected areas of the Amhara region.

Moreover, the International Organizations including WHO and other non-governmental Organizations, with the highest degree of fairness, should play a pivotal role in reaching the displaced and desperate people. Further studies with analytical study designs linked to the investigation of the extent of psychological distress are also required to be undertaken.

We would like to thank the data collectors and supervisors for their courageous efforts in collecting the timely data immediately after the withdrawal of the armed forces from the conflict areas. We are highly grateful to APHI for its financial support and its incomparable assistance in the arrangement of the field surveys.

ANC: Antenatal care;

AOR: Adjusted proportional odds ratio;

CI: Confidence intervals;

DIC: Deviance information criterion;

EAs: Enumeration areas;

EDHS: Ethiopian demographic and health survey;

ICC: Intra-cluster correlation;

OR: odds ratio;

PCV: Proportional change in variance,

NC: Postnatal carem,

MMR: Maternal Mortality Ratio and People Region

WHO; World Health Organization

Ethical clearance and approval were obtained from the institutional review board of Amhara National Regional State Public Health Institute (APHI). Permission to access data was obtained from the respective zonal health departments using written letters from APHI. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent and all personal identifiers were removed in order to keep the confidentiality of the information.

All the datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare no competing interests.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

GG drafted the proposal, did the analysis, wrote the results and prepared the manuscript. GM, GM, TZ and GY revised and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

GG has PhD in Public Health.